Clean Up the Arctic - Norway

"We protect the things in life that we love... In order to love something, first it is necessary to know it."

This mindset under pinned our expedition to Arctic Norway onboard Narwhal. We wanted to experience remote ocean beauty first hand while learning about the issues facing this part of the word and taking action to do our little bit to help

The idea was to take a group of people into their unknown to explore the arctic by sail boat. By doing so to immerse ourselves in the arctic environment, experience it first hand and foster a knowledge and love of the environment. It was also important that whilst doing so we should strive to make a positive contribution to protecting this beautiful environment. So the expedition objective of collecting scientific data as well as removing any marine litter from the isolated places that we would visit was set. So often an issue, it was really important to me that cost shouldn't be a barrier to being a part of this expedition so a crowdfunding initiative was set up to support one crew member in joining the expedition for just £5. An amazing response showed just how many people are passionate about taking action to protect our oceans, awesome! Now we had an eager crew ready to explore the arctic. I was confident that once they experienced the beauty of the environment for themselves they would fall in love with it and become advocates for it's protection. However a small voice in the back of my head kept telling me that the message of inspiring love for adventure in our wonderful world was too important not to share further and wider. Documentary film maker, Caroline Cote agreed to our join our expedition crew. Her mission would be to share the joy of being amongst nature, to document the challenges that we would experience this wild environment facing and share a positive message of how we can all be a part of the solution.

One of our main objectives was to survey and clean up marine litter found on arctic beaches. The most recent OSPAR marine litter survey data contains only nine data points for the whole of Norway and none in the area that our expedition would be visiting. This meant that we had no idea how big a problem marine litter would be in this area but highlighted how valuable any data that we would be able to collect would be extremely valuable.

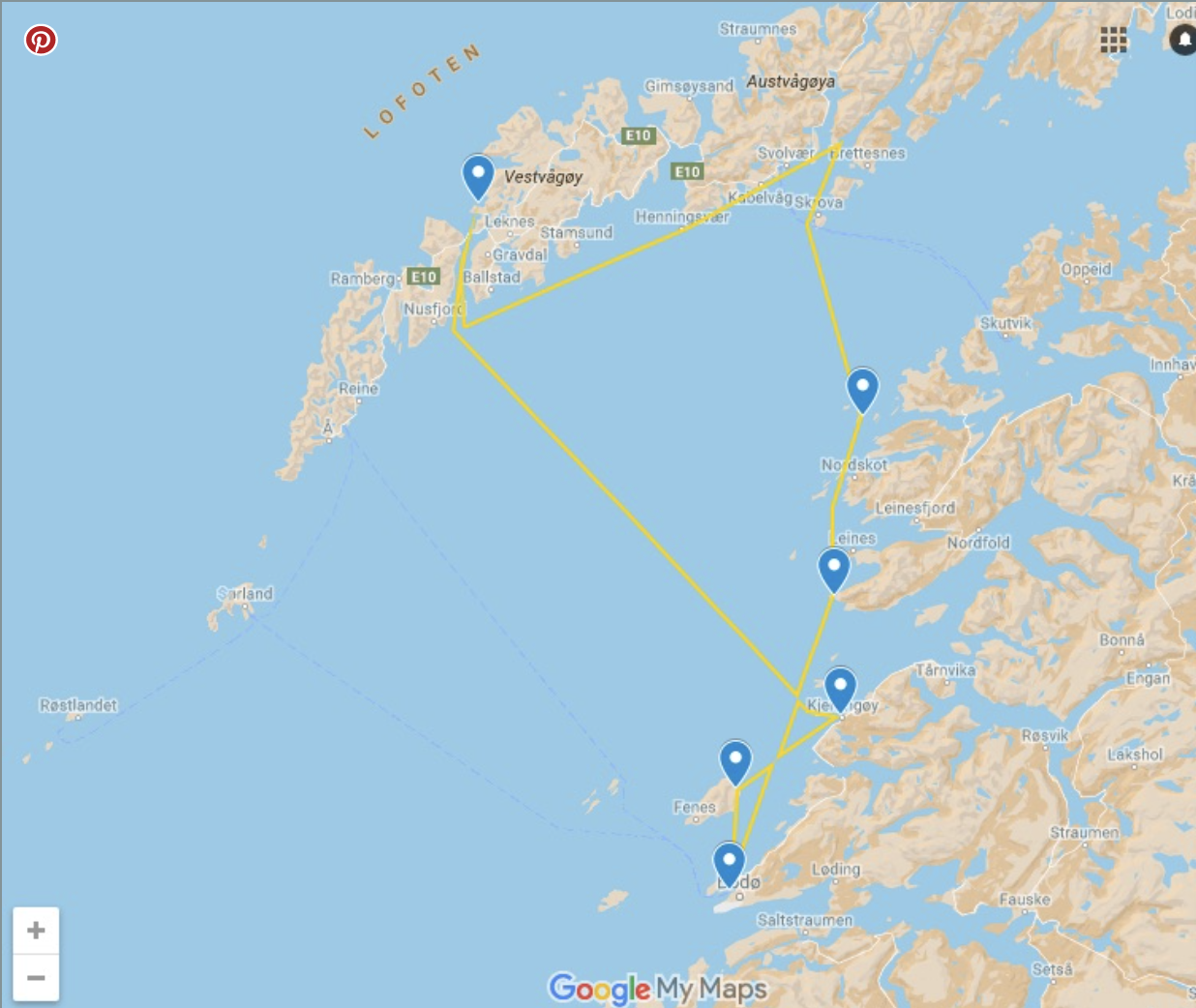

Our expedition took us through some remote parts of the Norwegian coast. Far above the arctic circle, the areas that we we travelled were frequently out of sight of human habitation however it soon became clear that they were not beyond the reach of human influence. Our route took us to five separate locations, each with different characteristics in how they are effected by the winds, waves and tides. Consequently the items that we found on each beach varied widely, but one thing that each location had in common was the sheer amount of man made plastic and other pieces of trash that were washed up on their shores. We found ourselves regularly removing so much rubbish that we couldn't fit it all into our boat. We were finding on average well over 200 pieces of rubbish for every hundred meters of beach. To put another way that equates to a piece of rubbish for every step you take along a remote arctic beach. I was shocked by the scale of the problem that we were witnessing

WHAT MAKES UP MARINE LITTER?

So what do you expect to find washed up on a remote arctic beach? It turns out that a vast array of human detritus finds it's way onto these beaches. The team collected everything from children's toys and an old oven to shotgun cartridges and car tyres. We even found a message in a bottle. This may not be considered very environmentally sound now but it held important information about how some much of this trash is reaching these remote beaches. The message had been released 11 years ago from one of the north sea oil rigs located much further south, between Norway and the UK. One theory of how marine litter makes it's way to Norwegian shores is that it is carried there by the ocean current known as the Gulf Stream. Sitting in our hands in the form of a message in a bottle was physical evidence of this process in action. Concrete, or should I say plastic, proof of how our oceans connect us all. Marine litter is not a local problem, but a global issue. I found it scary to think that litter entering the sea in UK is affecting wildlife in this beautiful wilderness but also in a way encouraging that no matter where you live, positive changes that you make will ripple out and benefit wildlife and communities far across the ocean.

Amongst these item oddities there were some distinct types of litter that kept turning up time and time again. By far the biggest category of items that we found were those made of plastic. Of these one of the most common was plastic bottles, ranging from water bottles to washing liquid containers. Exceeding even plastic bottles were the number of pieces of fishing gear washed up on to the beaches. Fishing line was abundant, as were small and not so small pieces of net and rope. These are doubly dangerous for wildlife since not only are they mistaken for food and ingested but they also pose an entanglement risk. The team also collected a large number of jerry can style containers. I was particularly distressed by how many of these were engine oil containers. Some of them even had engine oil remaining in them and slowly leaching out over the beach.

As part of the marine industry myself I feel sad that others who make a living from the ocean, whom I would except to be especially in tune with the need to protect it, can allow this to happen. Despite the legislation in place intended to stop waste oils entering the ocean and facilities widely in place across harbours and marinas something is still going wrong here.

A break down of some of the most numerous items that the team found on arctic beaches

In order to add value to the data that we collected, the team carried out the beach surveys according to the OSPAR beach litter monitoring protocol. This provides a comprehensive breakdown of litter categories allowing for comparison between beaches across the world, as well as some indication of the source of the litter, invaluable information in the quest to prevent it. Below is the breakdown of the total litter that we collected. Beach by beach data has been submitted to the Marine Conservation Society UK to add to the European database. It feels good that our expedition has been able to provide this data for areas that had previously not been represented in this way in the context of marine litter study.

MARINE LITTER ISN'T JUST ON THE BEACH

Travelling by boat gave the expedition a unique perspective in encountering marine trash as it moves around the ocean surface. Throughout the expedition all surface litter sightings were entered into a global database via the Marine Debris Tracker app. Those where it was safe to do so were brought on board to be disposed of properly. Including this plastic container of the ironically named 'Marine Clean'.

OCEAN SURVEYING

Although the sheer scale of the problem that we encountered meant that removing marine litter became one of the main tasks undertaken by the crew, the expedition wasn't all about the rubbish. There were also a number of other ocean survey projects to be undertaken as we traversed the ocean. One was to take measurements using a 'secchi disc' a standardised way or measuring the clarity of ocean water. The harder it is to see through the water, the more plankton the water is likely to contain and since plankton are the base of ocean food chains, the greater the potential for a healthy ocean. Cloud observations were made to help verify satellite derived data used for climate models. The survey that was always undertaken with the most anticipation was the cetacean (whale and dolphin) survey. It became a running joke of the expedition that after each half hour effort based survey, with all members of the crew scanning their section of the ocean for dorsal fins or whale blows to no avail was immediately followed by a casual sighting. Although we had reports of orcas in the vicinity, all of our sights were of harbour porpoises. The local fishermen report that over the last few years while extensive seismic oil surveying has been undertaken in the area the orcas have been scared away. Hence why there was considerable excitement when the locals started to sight orca in Vestfjord area again this year. Hopefully they are beginning a return to the area.

SPREADING THE WORD ON PLASTIC POLLUTION

The more research and planning that I undertook for this expedition, the more I became convinced that a pivotal objective of the expedition was going to need to be to share our experiences, the challenges facing our oceans right now and how we can all be a part of the solution with the world. It was fantastic that adventurer and documentary film maker Caroline Cote was able to join the expedition team. I am generally happier behind the lens, so it felt a bit uncomfortable at first to be wired for sound and explaining my feelings and passions to the camera. I had to remind myself of how strongly I believe that being in a position to experience these remote parts of the world is not something that I can just keep to myself but that sharing the message is the biggest contribution that I can make. I quickly adapted to the camera and before long was happily ranting in to Caroline's iphone about the state of the beaches. I am really excited to see how the film will look once it is completed. Having experienced the beauty of the environment and the amount of plastic on the beaches for ourselves I am even more passionate about spreading the message as far and wide as possible. Like local arctic environmental researcher, Berit, I also feel positive about this message resonating into the future and by sharing our experiences we really are helping to shift the tide against plastic.